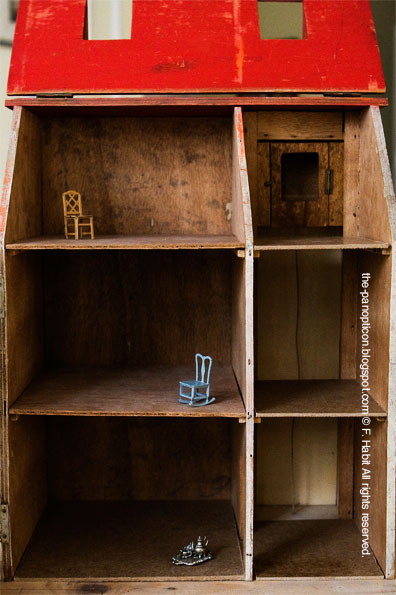

Years of unfulfilled longing meant that when I saw this at a local thrift shop

I decided it was coming home with me.

It's a home-built townhouse, front-opening. Age and provenance unknown. The style is decidedly of the first quarter of the twentieth century; but the windows that still retain their glazing are fitted with sheets of clear plastic. This could be a later replacement for celluloid/acetate, or it could mean a house constructed in the 1950s or later using an old set of blueprints.

However old it is, I love it. The exterior is agreeably battered and faded, with most of the pretty details intact.

I love the way the builder used just two colors and simple materials (wooden beads, bits of stock moulding) to achieve a richness of effect.

Inside, six rooms and an elevator. The elevator is operated via a crank in the base. It took some cleaning and oiling, but the car now travels up and down smoothly on the string while I hum "The Girl from Ipanema."

I've enjoyed imagining why the exterior was finished with so much care, but the interior was left completely unfinished. It might have been that a deadline (Christmas? birthday?) forced the doting amateur carpenter to deliver it half-made with a promise that interior decoration would follow. It might have been that the little owner was expected to do her own decorating, but never got around to it. It might have been that the miniature occupants got into such a dreadful fight over wallpapers for the front hall that they divorced and abandoned the property.

There's also a scenario involving alien abduction, but let's move along.

Whatever the reason, I'm happy the rooms are a perfect blank. In their current state, they have a melancholy I admire.

Also, were there even a scrap of 1930s linoleum, I'd feel honor-bound to preserve it. Since nothing period survives, I shall fill it up to my heart's content following my own fancy.

Of course that means needlework. A very small heap of very, very small needlework.

The scale of the house is not the 1:12 (inch-equals-a-foot) standard for modern "collector" houses meant for adults. It's 1:16, the old "play" standard for miniatures meant for children. Period furniture in 1:16 isn't impossible to find–the two metal chairs in the photographs are from Tootsietoy, a now-defunct maker once based here in Chicago–but it's uncommon, expensive, and often startlingly ugly. As much as possible, I want to make my own stuff.

I've already been knitting small, partly out of guilt. Remember Ethel? Ethel was supposed to be the doll who ended up in this, but proved unequal to the burden of all those layers. She was replaced by another model from the same agency. It happens all the time–even sample-sized gals aren't all built the same.

Ethel didn't complain, but I began to feel bad that she has ended up lying naked in a drawer for a year. She at least needs some frilly underclothes, lace-edged. I could buy doll's clothes. I could buy lace. But it's more fun to make them.

Enter the 00000.

This 00000 (also called five-aught, or 1mm) knitting needle was part of a bundle of antique double-pointed needles given to me as a gorgeous gift by a marvelously generous knitter I met while teaching at Sealed With a Kiss in Guthrie, Oklahoma. To give you some idea of the scale:

As I'm fortunate enough to have this blog read in many countries abroad, I put in as many small coins as I could find in the change box. I'm sorry that the selection was limited to places I've been. (Asia, Australia, South and Central America–I'm ready when you are.)

Now, standard needles go down to a completely hilarious 00000000 (that's eight-aught)–so I don't pretend I'm breaking any kind of record in working with a pair of five-aughts. Nutjobs like Betsy Hershberg (have you seen her new book, by the way? disgustingly good) would think nothing of this.

This is the finest work I've done yet, though. And it's fun. Like picking at a scab is fun.

Here's the edging for the bottom of Ethel's chemise, on the blocking board. The thread is DMC 80 Crochet Cotton, which is not much thicker than sewing thread.

If you're curious about the itttybittyknitty experience, some quick beginner's notes:

- Yes, it takes a while to find a comfortable grip. In fact, banish the word "grip" from your mind. Any attempt to "grip" one of these needles will result in a crumpled piece of wire. On the other hand, it seems to be normal and desirable that as you knit, the needles will take on gentle curves that fit your hands just so. I find this endearing. They're not just needles, they're obedient pets.

- I have seen (but do not own) knitting holders from the 19th century that protected fine needles inside stiff metal (sometimes silver) tubes. Having now tried to transport a pair of five-aughts in a standard knitting bag on the subway, I understand why.

- A magnifying glass is a great help if you are over sixteen. (I am.) Good lighting is vital, unless you enjoy gnashing your teeth until they shatter like cheap wineglasses. I have never been so grateful for my Ott Lite, which has both a huge magnifier and a clamp that holds my chart where I can see it.

- My antique five-aughts have blunt ends. I'm looking to play with some modern five-aughts and see if they have pointed ends. Pointy ends are a boon when you're trying to work a double-decrease. Fooling about with blunt-ended fine needles has kicked up my appreciation of 19th-century knitters another couple notches. I've seen photos of those women operating these things with gloved hands, which I think helps to explain the widespread Victorian notion of female hysteria.

It's a lace insertion for Ethel's chemise, yet another variation of the double-leaf motif that's been kicking around since the early 19th century.

I do a lot of knitting at this coffee shop. All the baristas know me. I've even taught a few of them the rudiments of knit and purl.

I was limping along, determined to make headway even without my magnifying glass and in dim light. I barely noticed the manager inching closer, pretending to wipe down empty tables but keeping one worried eye on me. When she was about two feet away she stopped and sighed with evident relief.

"Something wrong?" I asked, looking up.

"That is wicked small yarn," she said.

"You ain't kidding."

"Well," she said, "from over at the counter you can't see it. Or the needles."

"Really?"

"Uh huh. So you were sitting there...and moving your hands...and looking at them...and sometimes you were stopping to count...but it looked like you weren't holding anything."

"Oh, dear."

"I was sort of worried that maybe you were, I don't know–having some kind of knitting-related seizure?"

I reassured her that I wasn't.

But we all know it's only a matter of time.