Note: This is a very long and purely personal post. Please indulge me. On some occasions, this blog still needs to be the diary I intended. I want to write this all down quickly so I won't forget it, so I'm not going to spend a lot of time explaining every term, etc. And, as always when I write about Zen, all I'm doing is reporting my personal experience in as plain a fashion as I can. I write from a position of no authority. If you really want to learn about Zen, hunt down a qualified teacher or check out The Three Pillars of Zen

by Philip Kapleau Roshi.

When I first set foot in the Chicago Zen Center (CZC) back in March, I'd been reading about Buddhism on my own for a year, devouring any book I could get my hands on that didn't seem too superficial or too weird. The more I read, the more Japanese Zen seemed to call me. (I once thought Buddhism was a monolith. Not so. There are many, many sects–same as in Christianity. In Japan alone, even Zen has three major branches.)

My first sittings, for about two months, were with a GLBT Buddhist group in Chicago. They were a pleasant fellowship, and well-meaning, but ultimately I decided I wanted to work with a teacher. The group, which bills itself as non-sectarian was distinctly anti-Zen for reasons I still can't fathom. I asked the others about training centers in Chicago and was told, flatly, that aside from the Korean Zen temple in Lakeview that there weren't any and that, in any case, GLBT people do not practice Zen.

I chalked this up as yet another instance in which I and the mainstream GLBT community disagree about what is right for me. A quick hunt around on the Internet turned up the CZC, which not only seemed to offer exactly what I was looking for, but also happens to be about a ten-minute walk from my office.

After one visit, I suspected this was the place for me. After three, I was certain. The place is welcoming, but they don't give you a big hug when you come in the door. I was shown how to do prostrations, how to ask for the kyosaku during a sitting, how to do kinhin, and how to sit properly. And then into the zendo I went, to do it all best I could.

For somebody who has always been compelled to get even complicated things right the very first time, there have been moments of terror over the past nine months. Because, as I am beginning to comprehend, there's no such thing as a Zen prodigy. And at the CZC there's no hand-holding, no dumbing down, no gold star stickers for minute increments of progress. This is the real thing, not some hippy-dippy smiley-happy Easy Zen substitute, where the path to

satori is ordering a platform bed and ecru curtains from Pottery Barn. As a matter of fact, nobody seems to mention (or care about)

satori at all.

Sensei and the other members have been very kind to me as I've stumbled over my robe (and my own feet), bowed in the wrong direction after a sitting, got lost on the way from the Buddha Hall to the zendo, and (during one sitting I will never forget) slid right off my cushion with a deafening THUD because my entire ass fell asleep during zazen and I was trying surreptitiously to wiggle it around and wake it up.

I'm allowed to make mistakes, I'm expected to make mistakes. When they happen, I'm gently but firmly corrected or nudged in the right direction. It's like being a child, except that when I was a child in school my errors were punished far more harshly. I can remember so many times hearing a teacher yell, "I would have expected

[insert problem here] from any other child, but not from

you!" And now I'm not special, not special at all. What a luxury.

All of this led up to last night, and a ceremony called Jukai, during which I (and the rest of the community) took the precepts of Buddhism. I don't know how to describe this in terms that really make sense to people who haven't read a lot about Buddhism. It sort of reminded me of the once-yearly reaffirmation of baptismal vows in a Roman Catholic church. But for me, personally, it felt like a conversion ceremony. I was once a born Christian with an interest in Buddhism. Now I'm a Buddhist. A small but important (well, important to me) line has been crossed.

So that I won't forget them, I want to write down the superficial details of the night.

Jukai was preceded by what the CZC calls Temple Night. Usually, our practice isn't what you would call devotional. We meditate facing the wall, not the altar, and the altars are very small and simple. On Temple Night, sitting is done facing not only one, but many altars set up all around the center. This was my first Temple Night.

I arrived about 7:15 and was greeted by Mike, one of the practitioners who's been there...I don't know...forever?...who gave me a typical CZC orientation for a new occasion: it was whispered, about ten words long, and delivered only once. At this point, I'm used to that. I even like it. It keeps you alert.

I noticed that a scroll I haven't seen before, a standing Bodhidharma, had been hung in the Center's living room. It looked like it was a rubbing from a masterwork, but unfortunately I never got a chance to check it out up-close.

I went down to the men's changing room and discovered that Jukai is something like Christmas Eve in a Catholic church–people come out of the woodwork. I was lucky to get a hook for my pants and such, even though I was early as usual. Note to self: next time, show up at 7.

Sitting was open, which meant we could sit in either the Buddha Hall or the zendo; and we could get up and move as we wished (usually, the stages of a sitting are strictly timed and announced through the use of different bells and gongs). Mike had told me the altar for images of departed loved ones was in the zendo, so that's where I went first.

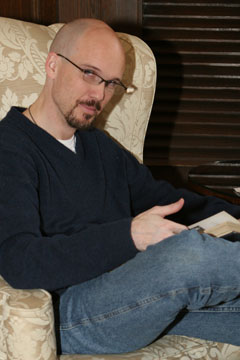

I had brought Uncle Mike's picture with me–the one from

this post. In the zendo everything was rearranged. Two arcs of mats faced a low, central altar of the many-armed Kannon (Bodhisattva of Compassion) against the west wall. There were a lot of photographs already on the altar. I added mine, bowed, and sat down, resisting the urge to stand there and examine the gorgeous figure. (The instincts of the art historian die hard.) It was odd, at first, to be facing the others instead of the wall, but I got used to it pretty quickly. Made a nice change. And then I noticed that everyone who came and went was doing prostrations to the altar* instead of merely bowing. Oops.

I sat, and felt that this sitting was really my time to remember and honor my uncle. My thoughts were very personal and I won't record them here.

After a time, I decided to move to the Buddha Hall and so got up, did three prostrations (without tripping over my robe!) to Kannon and headed downstairs.

My first sight of the Buddha Hall was so startling I had to stop for a moment and catch my breath. It's a low room, with dark pillars and walls and only small windows, high up. Normally the lighting is subdued, but on this night the only light came from hundreds of small candles on three altars and maybe six or eight smaller tables piled with offerings of fruit, vegetables, flowers, and bread.

From left to right, the altars were (I hope I remember this properly) Kannon (seated, gesture of the fist of wisdom); Shakyamuni Buddha (seated, zazen mudra) and Mahaprajapati (seated, gesture of fearlessness). I'm especially fond of that figure of Mahaprajapati. She was the Buddha's aunt/foster mother, and she was instrumental in persuading him to share his teaching with women. You go, girl.

In the dim light, robed figures sitting, sometimes moving to sit in a different place or do prostrations. Kinhin (walking meditation) at the back of the room. It felt...ancient. Imperturbable. Every so often, chanting. I discovered to my delight that both "Kanzeon" and the Heart Sutra are both now firmly in my brain, and about half the chant to avert disaster.

One thought that rang out loud and clear out of a quiet brain:

How happy and fortunate I am to be here.

Sitting in front of Kannon, quite close to the altar, I had a strong sense of

déja vu and couldn't stop from trying to puzzle out why. After about a minute it hit me. The overwhelming warmth, the peace in my chest were exactly those I'd experienced one Christmas, years ago, sitting in our darkened living room looking at the Nativity figures by the light of the Christmas tree. I've been trying to get back to that space, without success, for so many years. And here it was, perfect, as if twenty-plus years of angst had not intervened.

A round of kinhin, with chanting (something new for me–usually we're silent). I had never heard the chant before but recognized it (I think) as Sanskrit in praise of Shakyamuni Buddha. I need to go look it up to be sure.

And then, Jukai. I ended up quite by chance directly behind the mokugyo player, in the middle of things. As far as I know, I may have been the only person taking the precepts for the first time. Sensei led from the front. His sense of conviction was palpable. Another luxury: a teacher who believes what he's teaching.

I recited the Three Treasures, the Precepts, and the Bodhisattva Vows as directed. Meant every word of it. May not ever be able to live up to it, but I mean to try. Knelt, prostrated, bowed. And when Sensei read about this ceremony being the way in which "we enter the Buddhist family" I felt a tear roll down my cheek. I have so far to go, more miles than from here to the next galaxy before I'll even feel I've moved an inch, but at least I've started.

About the prostrations: the CZC's Web site explains them better than I could, in answer to the question of why there are figures on the altar if there's no "personal God" in our practice: "The Buddha (and the other figures) are inspiring to the practitioner. They embody, in a kind of metaphorical, crystalized manner, the enlightened, open mind that is our truest nature. When we prostrate or bow to a figure it is not a form of worship, but rather an affirmation that the purity that is represented by the figure before us is really within us, and we are lowering our smaller, limited ego before this all encompassing truth."