I've been ruthlessly clearing out boxes and bins for the past several months. I don't wonder why.

In August, after my grandmother died, we discovered that for years she had been treating her tiny house as a four-roomed, three-dimensional game of Tetris. Every inch of every closet, drawer, and cupboard was packed, neatly, top to bottom and back to front.

We–four adults–began our cleaning out by emptying closets. There were three. At the end of two days, we still hadn't got to the back of all of them.

The things we found. Oh, the things. My grandmother, proud daughter of the Great Depression, had learned early to never throw anything out because one day you might need it.

A bag of margarine tub lids (just the lids).

Eighty-three representations of the Virgin Mary in materials ranging from plaster to crochet

All the receipts for repairs to a car (I think it was a DeSoto) that probably made its last trip to the grocery store in 1962.

All of her pay stubs, from the 1940s to the day she retired.

A tea kettle with a burnt bottom. A roasting pan with a burnt bottom. A lid for a pot that disappeared, but which might fit another pot.

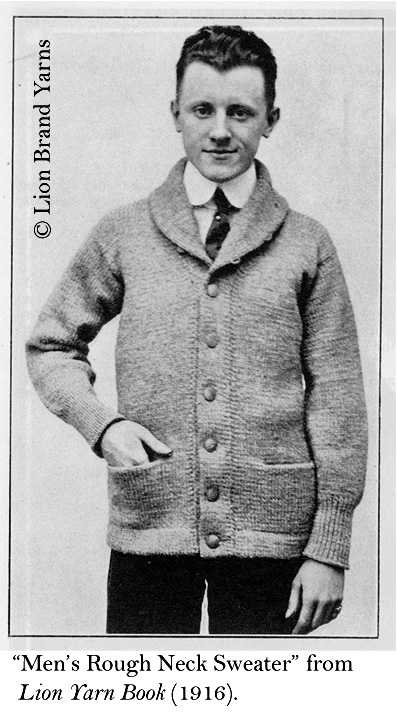

Thousands of zippers and buttons collected during eight decades of work as a seamstress and tailor.

Her prayer books. Her late son's prayer books. Her late mother's prayer books. Her late brother's prayer books. My grandmother was a religious woman, devoutly Catholic, and so when people died and left behind devotional paraphernalia, people said, "We should give this to Pauline." And my grandmother was certainly not going to chuck a crucifix, a Missal, or a guidebook to apparitions of the Blessed Mother in the trash.

It makes you think, seeing all that left behind. Some of it, I'm happy she saved. The trunk my great-grandfather (her father) brought with him as an immigrant in 1903 is here with me now, holding a heap of my knitted samples. It's a nice thing to have.

Other stuff, we groaned over.

Why did you save this? Why? And off it went to the dump or St. Vincent de Paul or the scrapyard.

Back at home, I looked around and felt like opening the front door to the general public and screaming COME AND GET IT! I started asking myself,

Why did you save this? Why?

One of the surprises I unearthed was a beat-up five-subject spiral notebook. Two hundred sheets, green cover. An old sketchbook, though with more than sketches inside. I date it to the year I would have been about ten, maybe eleven.

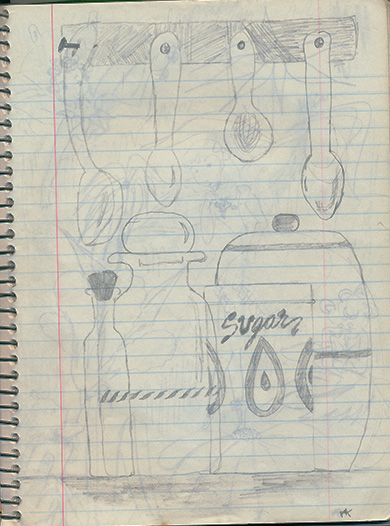

I found a Christmas list inside (I wanted Trivial Pursuit?), the recipe for my Italian grandmother's cookies, the start of a dreadful mystery novel (stolen diamonds), and lots and lots and lots and lots and lots of drawings.

I have to laugh. In this neighborhood, at this time, any kid who shows the slightest inclination to draw or paint is immediately presented with a plein-air easel, a set of oil paints, a tray of watercolors, a personal tutor kidnapped from a picturesque street corner in Montmartre, an agent, and a gallery show.

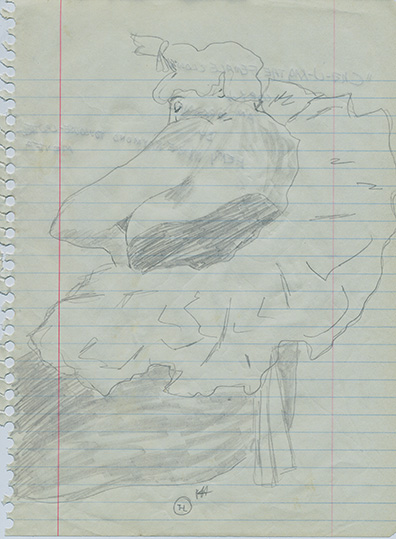

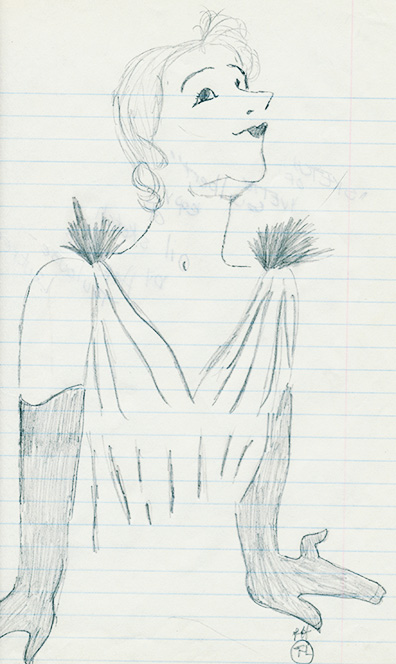

I drew on lined notebook paper with...whatever. Appears to be mostly Number Two pencils,* which seems about right. Art supplies cost money, and I didn't have any. And my art lessons consisted entirely of checking out art books from the base library and making freehand copies of stuff I liked.

What I drew made me laugh even harder. Looking at these pages, I wonder if I've changed fundamentally at all in the intervening thirty years.

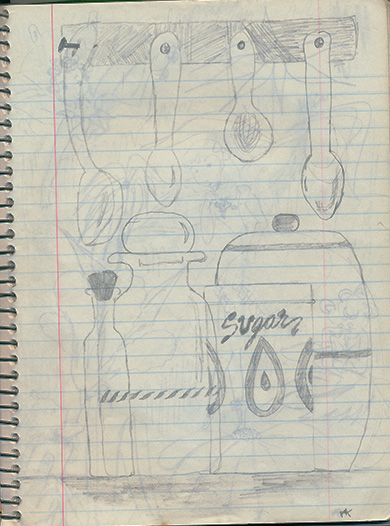

Vaguely nineteenth-century still lifes, mainly domestic, mainly culinary. Our kitchen never looked like this. I just wanted it to. I'd still like it to. (It still doesn't.)

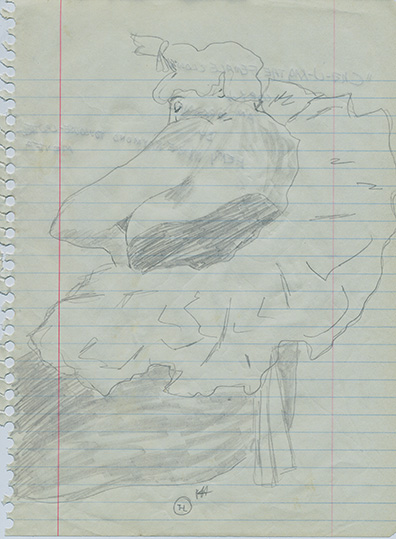

An obsession with Toulouse-Lautrec–again, the nineteenth century, writ large.

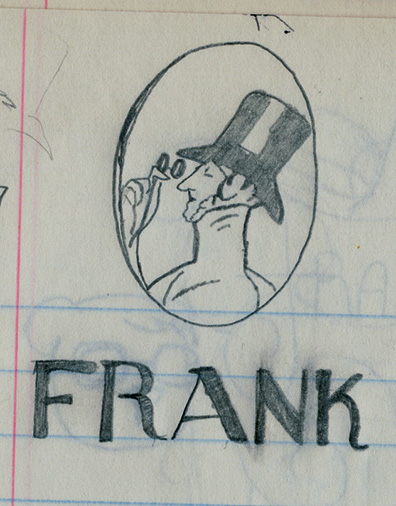

I already saw New York City as the Great Elsewhere–more chic, witty, urbane, and exciting than wherever we happened to be stuck.

I didn't understand half of what I read, but I forced myself to plow through everything in

The New Yorker from "Talk of the Town" to the back page with the hope that one day it would all make sense. (It did.)

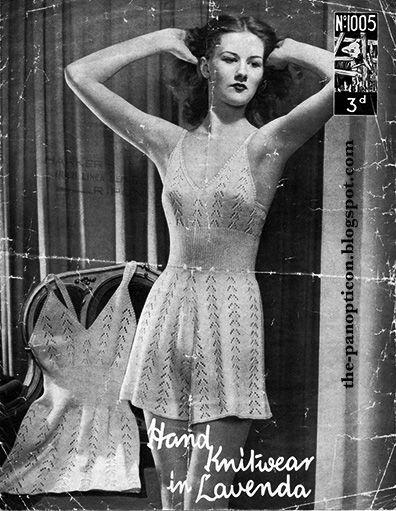

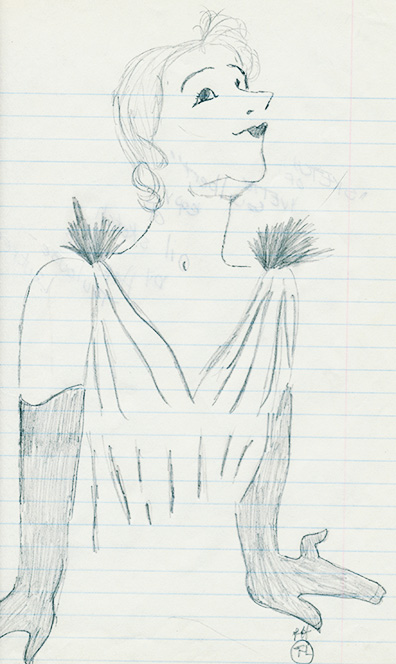

And costumes. Oh, costumes. Pages and pages and pages and pages of bustles, crinolines, lace collars, drapery, trains, capes, tiaras, gloves. I looked at Tintoretto's take on St. George and the Dragon and ignored both the saint and the dragon. What caught me was the fancy chick in the foreground.

I just looked at the original painting again and what gets me now is the muscular nude male in the middle ground. I'm sure I must have noticed him at the time, but I had

separate notebook (now long gone) for those sorts of drawings.

I'm not keeping the sketchbook. In fact, by the time you read this, it'll be gone. But it was fun to look it over one last time and see how far I have, and haven't, come.

*Young readers, Google it if you need to. Number two pencils are what we

used to use for making erasble marks on paper. There was erasable ink,

for a little while, but it never caught on.